Drawing by Sam Mahon Drawing by Sam Mahon Music by Chris Adams 7.00pm Saturday 10 February 2024 at The Piano, Christchurch Reviewed by Tony Ryan Tonight’s concert title is a reference to the composer’s wife who inspired much of the music on the programme and participated in the original performances of several of the works. Helen Acheson died last year, and this evening’s choice of music is very much in memory of her as a singer, musician and person. A total of eight works comprising thirty-two separate movements is an ambitious undertaking for a single concert, especially when all the music is by one composer with nine individual musicians in various combinations and permutations. And I imagine that, for most of the audience, everything on the programme is new – a daunting prospect for performers, composer and audience alike. However, the Quintet for wind and strings which opened the programme proved instantly engaging and absorbing. Each of the six movements had its own specific character, and demonstrated a wide range of imaginative contrasts, moods and textures. The opening phrase of horn player Alex Morton’s only appearance on tonight’s programme, gave the first movement Proclamation an immediate and communicative impact that set the tone for the whole work. Two of the movements are interludes for solo instruments and I found Jeremy Garside’s playing of the fifth movement Lament for solo cello particularly moving. Brief as it was, it remains my personal highlight of the entire evening. The one niggle I have with the performance of the Quintet is the placement of the violin in the ensemble’s stage layout. Perhaps being placed opposite the right-seated cello, instead of beside it, would have enabled the violin balance to emerge more equally with the more prominent sound of the other four instruments, especially in its almost inaudible pizzicato passages. ‘Character’ emerged as one of two key attributes of Chris Adams’ music tonight. Clearly identifiable and characterful motifs gave each movement an expressive appeal that kept the good-sized audience engaged throughout the two-hour duration. The other key feature of Adams’ music tonight is ‘intimacy’, a word which the composer himself used in his short spoken introduction. Although in most of the works that intimacy included elements of vitality, joy and occasional bursts of real exuberance, the Viola Sonata that ended the first part of the programme focused on the more introverted and thoughtful aspects of intimacy. Sophia Acheson and Jeremy Woodside gave us a committed performance of this elegiac piece, but it was the work that I found less effective than the others. But then, I have also often found that it’s the music I have to work hardest to assimilate that returns the greatest rewards over time. Soprano, Nicola Holt, was the only singer in tonight’s programme. Her light but clearly-focused timbre is ideally matched to the four works to which she contributed. A Song Cycle and Three Songs on Old Texts, both originally written for Helen Acheson, revealed Adams’ ability to respond intuitively to his chosen texts, with elements of humour, sentiment, spontaneity and directness that felt slightly more instinctive than in the more meticulously controlled instrumental-only pieces. The Dowland Fragments later in the programme allowed Holt’s higher tessitura to shine, almost as if these five very appealing songs were written for a different singer than the two earlier sets. The addition of a violin obligato part in these songs was beautifully and sensitively played by Sarah McCracken; I especially enjoyed her delightfully articulated lute-like accompaniment in the fourth song. Flautist, Hannah Darroch demonstrated total mastery of her instrument in three Art Miniatures where Adams’ imaginative exploration of the flute’s wide variety of techniques and effects was used for myriad and effective expressive diversity. A similar array of effects and techniques contributed to the appeal of Maud, a string quartet in which all four musicians highlighted the concert’s overall polish and professionalism, as well as both the consistency and variety of Chris Adams’ imaginative mastery of his craft as a composer. Two extracts from a chamber opera, River Lavalle, brought most of the musicians back to the stage to end the evening and, if we didn’t go out into the unseasonal rain exactly humming the tunes, there was certainly much to enjoy in this programme, and much that I’d like to hear again.

0 Comments

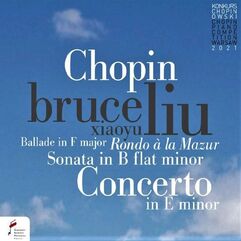

According to Eda Tang (Stuff – 24 March 2023), NZ Opera’s production of its newly commissioned The Unruly Tourists “is everything I want to see happen to classical music”. She goes on: “Too long has opera held onto tradition, languages that people pretend to understand, and upper-middle class etiquette.” I suppose that no offence is intended by Eda Tang’s rather confrontational tone, but ‘offensive’ is exactly how the phrase “languages that people pretend to understand” sounds. (We’ll overlook “upper-middle class etiquette” except to suggest that Ms Tang should witness the remarkably diverse audience mix at most opera performances.) But do first-language English-speaking operagoers really ‘pretend’ to understand the languages when Verdi and Puccini are sung in Italian, or Wagner and Strauss in German, or Bizet and Berlioz in French? I certainly wish I was more familiar with those languages when attending such operas, and even more so when watching international movies on Netflix, which I do rather often. But, like those movies, opera performances almost always come with surtitles or even, in many theatres, a choice of languages displayed on the back of the seat in front. None of us ‘pretend’ to understand other languages in these situations and even when we do (my French isn’t too shabby at a performance of Carmen), the surtitles are still helpful, even when the opera is in English. Does Ms Tang not realise that operas are written in the language of their creators (apart from an initial period of dominance by the Italians, who created and developed the genre – what a debt we owe them!)? As an experienced reviewer myself, I try to avoid making assumptions about things that I’m unsure of or unfamiliar with, but reviewer Tang confidently asserts that The Unruly Tourists “moves opera into modern contexts”, as if to suggest that this is something new. She appears completely unaware of some very significant evidence that totally annihilates such an assertion. Opera composers, librettists and directors have been moving opera “into modern contexts” for centuries, and continue to do so even more in our own time. Handel’s exceptionally popular eighteenth-century operas (frequently based on characters and historical events from ancient civilisations, and written by a German composer in Italian for an English-speaking audience) were, from the outset, staged with contemporary costumes and sets, and with significant and deliberate references to the social and political climate of Handel’s own era. How often since then have we seen Handel’s operas or, say, La Traviata or La Bohème or Cosi fan Tutte or the Ring Cycle set in our own or recent, or even a future or fantasy time? Well, I and multitudes of others have, but it seems that Ms Tang has not. And the whole reason that those operas have survived and remain hugely popular (unlike hundreds of others, pertinent and fashionable at their time, but now forgotten) is because of their enduring and universal relevance. As the great Scottish director Robert Carson says, regarding his penchant for staging operas and plays in modern dress and settings, “We mustn’t let the audience off the hook; people need to see themselves portrayed on the stage”. Such operas may not always or easily appeal to the faint-hearted who are unwilling to delve deeper to uncover their truths and riches, or to seekers of a quick-and-superficial entertainment fix, but their spiritual and artistic depths and resonances are at the heart of our humanity and broader cultural consciousness. Even more importantly, Eda Tang seems wholly oblivious of the vast range of operas written in English and to the huge number written in a wide range of languages in our own time. Apparently she has missed the recent innovative and thought-provoking productions by Christchurch’s Toi Toi Opera, which not only put twentieth century English language operas in front of us, but demonstrate some truly imaginative ideas on how to make the genre of opera directly relevant to its audiences. Within the world of ‘classical’ music, depending on how you interpret that word (It is, after all, just a label coined to try to identify certain characteristics of a body of musical works), there have been many recent innovations that blur the traditional lines between opera, sonata, symphony and all manner of other forms that have acquired sub-labels intended to distinguish particular characteristics. The concept of ‘opera’ has acquired an understanding of being a music-theatre piece involving a particular style of singing and including an orchestra, and there are many new examples that easily fit that concept. Opera companies and music festivals all over the world have brought us a hugely diverse range of new operas – to name a few of the more high-profile examples: Thomas Adès The Exterminating Angel, John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles, Philip Glass’s The Voyage, Satyagraha and Akhnaten, Tan Dun’s The First Emperor, John Adams’ Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic, Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, Anthony Davis’s X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X, Nico Muhly’s Two Boys and Marnie, Kaija Saariaho’s L’Amour de Loin – the list is endless! And in the last little while, New York’s Met Opera has commissioned and staged Ricky Ian Gordon’s Intimate Apparel, Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice and, most moving and extraordinary of all, Kevin Puts’s The Hours. And here in New Zealand, Kenneth Young’s The Strangest of Angels was premièred less than a year ago. These operas range in their subject matter from political and social subjects, to plots exploring racism, sexuality, ethical dilemmas and so much more. Not having had an opportunity to see NZ Opera’s The Unruly Tourists myself, I cannot comment on Eda Tang’s assessment of its merits, but based on the short promotional and news-media audio-visual clips that I’ve seen, when Tang states “If you like The Book of Mormon, King George III from Hamilton the musical and are a self-professed JAFA, you’ll probably enjoy The Unruly Tourists”, I’d say she’s probably bang on the nail in terms of theatrical and musical type. But her reference to being “a self-professed JAFA” surely trivialises the creators’ aspirations by parochialising the whole shebang. And would either of those two examples (The Book of Mormon and Hamilton) pretend to be opera? Both are consistently and universally referred to as ‘musicals’ or ‘musical comedies’, so why is The Unruly Tourists referred to as an ‘opera’? Is it because of its being produced by an opera company? Or is because people like the reviewer just want it to be one? And when Ms Tang asks “did they really just set those words to [sic] an opera?” and then goes on to assert that only in Aotearoa would you hear certain colloquialisms that she quotes “set into [sic] classical music”, well, I guess there’s no harm in blurring the boundaries if you’re clear about the characteristics of the different genres; but I’d certainly take issue with any idea that such colloquialisms are in any way new to musicals, opera, or any other theatrical form. But why does she call it ‘classical music’? It may well be (. . . or not?), and anyway, what does it matter? But Tang appears to want to take aim at her skewed idea of ‘classical music’. In any case, she seems to be aligning The Unruly Tourists with a different musical genre with which she has a much easier affinity. So, if that is what she wants “to see happen to classical music”, I can only infer that the statement at the start of her review, and which I’ve used as my headline, indicates a rather self-important and condescending antipathy to a huge body of the profoundly eloquent and powerful musical treasures of our diverse world. And many of those treasures are riotously comic; that is part of their profundity. Finally, as for suggesting that we can enjoy a cheap night out at The Unruly Tourists rather than “fork out hundreds to go to watch La Traviata”, I guess the same applies to the recent visits by Ed, Elton and Rod. Again – is Eda Tang’s ‘review’ deliberately offensive, or is it just sloppy journalism? Can we no longer expect genuinely informed, considered, and knowledgeable evaluation of the performing arts from some of our mainstream media?  My Recording of the Year could also be described as my Performance of the Year, or even perhaps, in this case, of the decade and beyond. But who am I to judge? And even if my opinion counts, what about all the recordings and performances that I don’t personally experience? Luckily, publications like Gramophone, Fanfare, BBC Music Magazine and various online platforms provide extensive guidance to the numerous recorded performances that become available each year, and their annual awards highlight many rewarding performances. Gramophone’s monthly Editor’s Choice and annual Recordings of the Year awards have led me to many treasured recordings that I might otherwise have missed. For me, last year’s Gramophone Awards included just one recording that struck a special chord – an absolutely stunning (“sensational” was Gramophone’s word; and I couldn’t disagree) Mahler Symphony No. 7 from Kirill Petrenko and the Bayerisches Staatsorchester taking out the Orchestral Recording of the Year. The winners of the choral and instrumental categories are also treasurable, if not quite the knock-out that the Bavarian orchestra delivers. And I do look forward to exploring the same conductor and label’s Bayerische Staatsoper video recording of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt which won the opera category as well as being voted Record of the Year. Because, although it’s possible to listen to almost all the winners and other nominees with the benefit of a streaming subscription, I don’t have access to the video format in the same way. The preamble to Gramophone’s 2022 Awards issue states that recordings reviewed between June 2021 and May 2022 are eligible for selection, which immediately limits the choice to recordings that Gramophone has reviewed. One might think that any recording considered worth reviewing would surely come their way, but my own personal Record of the Year, along with many others (e.g. those released on the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s own label), was never evaluated by Gramophone’s reviewers. So, why Bruce Xiaoyu Liu’s Deutsche Grammophon recording of selections from his winning 2021 Chopin Competition performances didn’t make the cut, is beyond me. Praised in Gramophone’s December 2021 issue as “ . . . simply one of the most distinguished Chopin recitals of recent years, full of maturity, character and purpose”, along with similar superlatives from a reviewer who also hoped for the release of an album of more of this pianist’s performances from the competition. In February 2022, that recording came, not from DG, but on the Frederick Chopin Institute label. And that is my recording of the year which none other comes within miles of, however special it might be. But it’s an album that seems to have received no awards at all let alone even a review in Gramophone. Everything on both discs is equally breathtaking – an infrequently heard Rondo à la Mazur that becomes a masterpiece in Liu’s hands; an F Major Ballade that combines poetry and drama so intuitively that it’s like hearing it for the first time; an Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise Brillante that Gramophone’s reviewer declared to be the best he’d ever heard; an A Flat Waltz whose technical demands are mastered so completely that it sparkles and dances as never before – but it’s the magic of Liu’s performance of the E Minor Piano Concerto which is simply jaw-dropping! It’s as if he’s managed to get inside the composer’s inspiration at the very point of its taking flight, and he delivers a performance of such charisma and heart-in-throat dancing, singing, joyful, and instinctive fervour, that a long familiar and oft-heard favourite comes vividly to life in a way that I find difficult to adequately describe. For now it’s the only performance I can listen to, although long-cherished recordings by Ashkenazy, Zimerman, Argerich, Kissin, Perahia, Pires and others, including the previous Chopin Competition winner Seong-Jin Cho, line my record shelves. No doubt there are knowledgeable sages and guardians of various holy grails who will never allow that anything can surpass, say, Zimerman or Pollini or Rubenstein or Lipatti, or any number of others, but for now, for me, Liu reigns supreme. At the 2021 XVIII International Chopin Piano Competition many other fine pianists gave excellent performances of this same concerto, but listening to those or watching them on YouTube, the superior inspirational magic of Bruce Liu’s playing eludes them. His ability to subtly colour or highlight a passing phrase or figuration frequently has me smiling or even laughing out loud at the sheer wonder of it; and it’s all done with such an intuition for light and shade, delicacy and ardour, tonal silver or velvet, and all manner of other intangible contrasts. As I write, the recording is playing again and Liu has just reached his entry in the concerto’s second movement Romance and, although I’ve played the disc so many times already, its heart-felt expressive quality hasn’t diminished in the slightest. Each time I play the recording, now always several self-disciplined weeks apart, I worry that the magic will be lost but, thankfully, there it still is. I first heard and saw Liu’s concerto performance on YouTube after the competition and wondered if it would retain the same mesmerising impact in audio only. I need not have feared; whatever visual wizardry enhanced that first experience remains fully present when just listening. And there too in this live performance is the smiling and idiomatic support from the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Andrey Boreyko, and the elated shouts of acclaim from the audience even before the orchestra has played its final chords, and then they’re on their feet with a seemingly involuntary need to demonstrate their enraptured appreciation of a performance of a lifetime. As one commenter on the YouTube video observes – “This dude is so good the lady in the wheelchair stands up to applaud”, and so she does, such is the miracle of Bruce Liu’s performance.  In the twenty-five years or more that I’ve been a professional music and theatre reviewer, none of my reviews have been censored. Some have been slightly edited due to space constraints, but none actually censored – until now that is! Yes, there have been many face-to-face comments from friends, acquaintances, colleagues and others, and a few private correspondents who have agreed (mainly) with my published reviews and acknowledged my insights. A few people have said they don’t agree with everything I’ve said or written about any particular performance, but only one, a certain Melissa Lo (whose pronouns and age I can only guess at – so I won’t), who, in the comments below my Theatreview review, disagreed with my appraisal of a production of the musical Wicked so vehemently that all rationality was abandoned by presuming my pronouns, skin colour and age, and ‘guessing’ (Melissa’s word) that I was “a bitter old white male who didn't understand the magical world of Oz”. Melissa went on to declare: “I wasn't at the performance and plan to see it this week,” and continued “I don’t doubt that I will be cheering for the whole cast and crew for their amazing performance”. I resisted the temptation to assure Melissa that, unlike him/her/them, I write my reviews after attending a performance, not before. And I don’t think anyone who knows me would call me “bitter”. Some of my other reviews might help to change Melissa's mind, so perhaps my review of another contemporary musical from the same directors might be a good place to start. But maybe Melissa is right about my not understanding the “magical world of Oz”, a land in which author L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), as reinterpreted in Wicked by Gregory Maguire, sees life through fairy-tale analogies and parables to assist our grasp of the mysteries of life, even if we can never fully understand them. But it seems that Melissa is much more confident of having a thorough understanding of that "magical world". Personally, I need to draw on a much wider range of experience, knowledge and associations in order to assimilate my published responses to performances. From time to time a musician or music organisation (rather than the usual print, radio or online news media) commissions me to write a review for their own promotional or online platform in the hope that it will then be more widely published, which it often is. Several years ago, the late Christopher Marshall, whose Christopher’s Classics series has reached its twenty-eighth year of providing Christchurch audiences with the very best of Aotearoa’s musical talent, asked me to review the concerts in his series, which I have been doing now since 2017. These days, most newspapers and other media in New Zealand no longer allocate budgets to pay professional reviewers, so most of those reviews have been published on Christopher’s Classics own website – an increasingly common scenario. Christopher always knew that I would maintain my honesty, integrity and unbiased views. He understood that, while some reviews would be politely positive, others might be glowing raves and a number would contain reservations. He often talked to me about what he agreed or disagreed with, but he always valued and respected my knowledge and perceptions. After all, a reviewer is just an individual with an informed opinion, and a different individual will always have their own personal response. All we can do is react to what we see and hear, to describe that response and to say why we have arrived at a particular point-of-view. As a performer myself, I have learned a great deal from others’ opinions, especially when they diverge from my own. But earlier this month, for the first time in my reviewing career, Christopher’s Classics chose not to publish my review of their latest concert featuring cellist Andrew Joyce and pianist Rae de Lisle. They paid me as usual, but I now realise that I could have earned my few dollars by being far less considered, telling the performers and promoters what they wanted to hear, and by taking less trouble than the three hours of writing, research, refining and polishing. I have no problem with them disagreeing with me – I’ve often disagreed with other reviewers’ comments myself; but to fail to publish the review without giving any reason, let alone communicating with me at all about their decision, is surely discourteous and disrespectful at best, and censorship at worst. As I said above, a review is just my own opinion. Every individual member of an audience responds differently to any given performance, and I sometimes wonder if, say, the person in front of me, applauding with vociferous enthusiasm, has genuinely found the music-making as stimulating as I have found it lacklustre, or, when I am moved to the core by a performance, whether anyone around me has shared the same, sometimes life-changing experience. A renewed era of censorship has emerged since the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. Certain Russian musicians have been censored and censured; some musicians have removed Russian works from their programmes (e.g. see my previous post regarding the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra) while others have added Russian pieces to their programmes, especially by composers like Shostakovich who could be said to have written the book regarding musical censorship and political oppression. In this regard, my role as a music reviewer once again came under attack when, back in March, I criticised NZ Chamber Soloists for dropping Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 1 from their concerts because, according to them, it “celebrates Russia as a superpower”. I was contacted by the Christchurch Press, as one of their reviewers, and my disagreement with NZ Chamber Soloists’ decision was quoted along with similar comments by others. As it happened, the group’s Christchurch concert was scheduled to be hosted by Christopher’s Classics who, in an email to their subscribers, expressed their disappointment in The Press article and named me as one of the offenders. My review of the ensemble’s concert in June was as subjective in my personal response and as objective in my analysis of the music and its performance as always, but the replacement of Shostakovich’s trio by a rather innocuous and conventional work by Armenian composer, Arno Babajanian, remains, in my view, an insidious example of the growing ‘cancel culture’ style of censorship which is becoming an increasingly worrying trend.  A protest by musicians in Colombia against the government A protest by musicians in Colombia against the government In his recent (2019) book Rough Ideas, British pianist Stephen Hough ventures his opinion that “I think it is safe to say that most musicians have predominantly liberal, left-wing views . . .” and, although he claims a degree of political naivety, his book refers to a wide variety of issues that can readily be regarded as political. The fact that so many musicians of both the past and the present often take a stand against various aspects of the political status quo, certainly supports Hough’s statement. Even some of the composers who feature in parts 1 & 2 of my Politics in Music series were political and subversive activists. Richard Wagner went into exile from Germany for fifteen years following his advocacy of revolution and his participation in the failed Dresden Uprising of 1848-49. The pianist and composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski, an outspoken supporter of Polish independence, became Poland’s third Prime Minister in 1919 and was a signatory of the Treaty of Versailles. Mention of Polish independence brings another great Polish pianist to mind. In April 2009 Krystian Zimerman, who has remained one of the world’s most highly regarded pianists since winning the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1975, launched a tirade against the U.S.A's plan to establish a missile defence shield in Poland. At a Sunday night concert in Los Angeles’s Disney Concert Hall, the normally quietly-spoken Zimerman told Americans to “Get your hands off my country”. Many in the audience cheered, some shouted at him to "shut up and play the piano" and, as several people walked out yelling abuse, the pianist told them to “keep marching like the military”. He would no doubt have something to say about the U.S.’s part in supporting the election of Volodymyr Zelenskyy as president of Ukraine in order to facilitate a military presence even closer to the Russian border. That protest wasn’t the first time that Zimerman had spoken out in the U.S. against their policies. In 2006, before playing a Beethoven sonata in Baltimore, he denounced the Guantánamo Bay prison, and later the same year announced that he would not return to the U.S. until George Bush was no longer in office. Zimerman’s attitude to American military policy was probably augmented by incidents involving his personal Steinway piano, which he travelled with on major recital tours. Soon after 9/11, Customs officials at JFK Airport were suspicious about the glue in the framework of his piano, so they seized it and destroyed it! A few years later he tried bringing his new piano into the U.S.A. and Customs again confiscated it, holding it for five days and disrupting his performance schedule. Hungarian pianist András Schiff believes that “it is the responsibility of every politically informed artist to speak out against racial injustice and persecution” and argues that “artists, as sensitive individuals with a societal function, cannot be separated from political affairs.” Along with statements about politics in Austria and Hungary, Schiff’s public condemnation of Hungary’s government and its long-time Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, accusing them of racism, anti-Semitism and neo-fascism, has prevented his return to his native country since 2012. Staying with pianists, one of the world’s currently most highly regarded musicians, Igor Levit, is a familiar face on mainstream Germany TV where he participates in political panel discussions. His humanitarian views are aired on his very popular Twitter account on a daily basis, and he likes to play Beethoven’s Ode to Joy at the annual Green Party conference. Levit also played Beethoven’s Ode at the start of his recital at the opening night of the 2017 Proms in London, as a musical expression of opposition to Brexit. His humanitarian political views, and his direct involvement in politics have taken him to refugee camps and have even attracted death threats. He believes that, although “music has astonishing powers of communication, it cannot be a substitute for calling racism ‘racism’, or calling misogyny ‘misogyny’. It can never be a substitute for being a wakeful, critical, loving, living, and active citizen.” Conductor Daniel Barenboim is somewhat notorious for using the conductor’s podium as a platform for expressing his political views. Also at the 2017 London Proms, after a performance of Elgar’s Symphony No. 2, Barenboim told the audience that "Elgar was a pan-European who would not have supported Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union". He went on to lecture the audience about the dangers of Britain’s “isolationist tendencies”. Then, at the end of this year’s Vienna Philharmonic New Year Concert, in addition to the traditional wishing the audience a happy New Year, Barenboim proceeded to condemn, as so many other musicians and musical organisations have since done, the impending threat (now an all-too-real catastrophe) of a Russian invasion of Ukraine. But Daniel Barenboim’s most constant political activism is directed at Israel’s aggression towards Palestine and the Palestinians. On his website he outlines in detail his opposition to Israel's policies regarding Palestine. As a Jew and an Israeli citizen himself Barenboim is ideally placed to express such views without fear of having those views glibly dismissed as anti-Semitism. At a government ceremony in Tel Aviv, when receiving the 2004 Wolf Prize, his acceptance speech openly criticised Israel’s policies and actions concerning Palestine. As the audience applauded his comments, Israel’s Minister of Education, Limor Livnat, told them to “control yourselves” and condemned Barenboim for using the award ceremony to criticise Israel. The conductor’s efforts to unite Israeli and Arab musicians through his East-West Divan Orchestra is well-known. The Israel-Palestine situation has featured widely in protests by musicians and concert-goers around the world. In 2011 the London Philharmonic Orchestra suspended a group of its players for publicly stating their opposition to the inclusion of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra at that year’s Proms. Their suspension sparked widespread support for their protest from musicians and artists throughout the UK. The Israel Philharmonic has also been at the centre of many other protests, one resulting in the cancellation of its visit to Sydney in 2019. Since the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the music world has reacted emphatically with numerous demonstrations of support for Ukraine and condemnation of Russian musicians who fail to speak out about the actions of their country. In New York, the touring Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra sacked their pro-Putin Russian conductor Valery Gergiev and piano soloist Denis Matsuev, but continued to play their three concerts, including an all-Russian programme, with a different conductor and soloist. The following week, Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducted the cast, chorus, and orchestra of New York’s Metropolitan Opera in a performance of the Ukrainian National Anthem before the opening performance of its new production of Verdi’s Don Carlos, an opera whose very plot centres on the foreign invasion of an independent sovereign country. In the rush to condemn Russia, some went a bit too far. The Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra in Wales faced a considerable public backlash when it dropped several Tchaikovsky works from a programme in March. As a consequence the orchestra announced that it would be retaining scheduled works by Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Rimsky-Korsakov later in the season. This edition of Troubleshooter includes just a very few of the many examples of politics in music, in music-making, and the music-makers themselves. It demonstrates the naivety and absurdity of any suggestion that politics has no place in music. Music, like all the arts, expresses every aspect of life, from love and betrayal to patriotism and oppression, and every human condition in between; and it will undoubtedly continue to do so as long as it has any purpose at all.  © Karyn Taylor-Moore for Toi Toi Opera 2022 © Karyn Taylor-Moore for Toi Toi Opera 2022 Toi Toi Opera Barber – Knoxville Summer of 1915; A Hand of Bridge; Bernstein – Trouble in Tahiti Director: Matthew Kereama Musical Director: Rachel Fuller Singers: Matilda Wickbom – John Bayne – Emma Gilkison – Nigel Withington – Alex Robinson – Katherine Doig – Helen Acheson In February last year, we, the opera stalwarts of Christchurch, headed along to The Great Hall of the Christchurch Arts Centre for the debut production of a new local company – Toi Toi Opera. Billed as Suor Angelica (Puccini) and Elegies (Britten, Butterworth, Vaughan Williams), it rather surprised us with its innovative, thought-provoking and imaginative approach to opera presentation. With its high production values, along with a well-chosen cast and creative team, it projected a considerable emotional and artistic punch. In this new double bill those same qualities abound. The concept emerges, not so much as a double bill, but as an integrated and cleverly matched combination of three American pieces in which Toi Toi’s creative team have played as much a part as the composers and librettists. All three works share a domestic intimacy and a degree of commentary, sometimes overt, sometimes implied, on the elusiveness of the American (human?) dream. Samuel Barber’s 1938 lyric rhapsody Knoxville: Summer of 1915 is one of the great masterpieces of American music and, in Toi Toi’s ingenious realisation and Emma Gilkison’s convincing performance, it proves a logical and effective prologue to the same composer’s ten-minute 1959 opera A Hand of Bridge in which the two couples (Helen Acheson, Nigel Withington, Katherine Doig, Alex Robinson) despairingly and, in the context of theatrical subterfuge, humorously reveal their supressed dreams and desires as they live out their somewhat routine and unfulfilled lives. All five singers in this first part of the programme portray their characters with persuasive commitment and vocal distinction and, while Katherine Doig stands out for her willingness to communicate a more forthright and characterful projection of both voice and character, the others have a tendency to restrain their projection, perhaps as a way of conveying the characters’ repressed aspirations. In particular, in Knoxville, I would have welcomed a more expressive and opulent expansion of the higher, arching phrases from Emma Gilkison, where she has a tendency to pull back. At times her projection and diction are so restrained that the emotional flow of the music loses a degree of its impact. A slightly more fluid tempo might also highlight the dramatic contrasts of the piece, especially in the transition into the magical episode where the singer describes the family lying on quilts on the grass. That same restraint is noticeable in the Greek-chorus-like trio commentary in Bernstein’s 1952 one-act opera Trouble in Tahiti. It’s not just a matter of volume, but of projecting the spirit of the musical and dramatic style of this feature of the score. Bernstein’s writing is full of subtle dynamic swells and falls for this ensemble (Emma Gilkison, Nigel Withington, Alex Robinson), but here everything is subdued and, although it seems to be a deliberate musical decision, it needs just a bit more . . . well . . . oomph! But it’s beautifully sung – the blend of the three voices, intonation, stylistic accord, and physical vitality and coordination are impressive and often very entertaining. The final scene where the trio represents the American dream peering in through the living room windows is particularly effective and dramatically compelling. The two principal singers in this work embrace their roles with total conviction. John Bayne is a suitably self-opinionated Sam who has the requisite vocal and dramatic skills as well as the ideal physical attributes for the part. When dressed as the corporate businessman, Bayne tends to be a little wooden in his portrayal compared to his more liberated and amusing characterisation in the gym changing room. But he is always convincing in his representation of the husband in an increasingly dysfunctional marriage. As his wife Dinah, Matilda Wickbom’s singing and acting makes her character the more sympathetic partner, although she too is not without flaws. Wickbom’s “I was Standing in a Garden” aria is, for me at least, the highlight of the evening – touchingly and beautifully done. And her contrasting “What a Movie” solo demonstrates an ability to find and communicate the diverse vocal and character facets of the part. A superb onstage quintet of instrumentalists, led with vitality by musical director Rachel Fuller, supports the stage performances with pizzazz and subtlety as required, although they too, at times, are a little more subdued in their projection than I would have preferred. Set, lighting and costumes are excellent – appropriate, but with just that inspired element of subtle caricature that highlights the stereotypes represented in the works themselves. Matthew Kereama’s direction ensures that the writers’ intentions are allowed to unfold without any meddlesome intervention, so that the music, acting and overall concept works superbly. Toi Toi is certainly a company to watch – not only talented and professional, but innovative, imaginative and adventurous in a way that will surely develop a growing following as its reputation spreads.  Photo - Petra Mingneau Photo - Petra Mingneau The Strangest of Angels – Composer: Kenneth Young (with Anna Leese); Librettist: Georgia Jamieson Emms New Zealand Opera – Anna Leese, Jayne Tankersley, Members of the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra Conductor – Kenneth Young; Director – Eleanor Bishop There comes a point – the interlude before the third and final scene of Kenneth Young’s new opera The Strangest of Angels – when at last the music sings and dances. The orchestra launches into what almost sounds like a reference to the Habanera from Carmen which then quickly evolves into a tango of distinctive originality and, musically at least, for the first time in this hour-long opera, real personality. Here at last is the composer of Dance (one of my favourite pieces by a New Zealand composer) and Virgen de la Esperanza. Then, as that final scene progresses the musical invention remains at a notably more significant level of importance than seems evident in the earlier scenes. Until that point The Strangest of Angels is primarily about the plot, the characters (NZ writer Janet Frame and fictional Seacliff psychiatric nurse Katherine Baillie), the psychology and the stage performances, while the music, both instrumental and vocal, responds to the narrative rather than drives it. In the first two scenes it’s almost as if librettist Georgia Jamieson Emms has written a play that needs no music. Surely the art of the librettist is, to a large extent, to trust in the composer’s ability to drive the emotional and dramatic impetus of an opera; to know what to put into words and what to leave to the music? So, what we have for the most part is recitative-like, predominantly syllabic vocal parts underlined by an instrumental commentary that reflects what is already expressed in the text and the singers’ performances. These on-stage performances are certainly vocally and dramatically convincing. Anna Leese in particular maintains a full-toned and richly coloured vocal presence and uses both her vocal powers and stage presence to project a convincing and sympathetic character. There are times when the tessitura of her role as nurse Katherine Baillie tends to sit for lengthy periods in the higher range, but that makes the splendour of her lower register all the more dramatically effective when required. The audience responds readily and audibly to her ability to shift quickly from authoritarian aloofness to sarcastic humour, and her attention to every nuance of the text is consistently fluid and detailed. It’s a performance that, in the end, draws us in and earns our sympathy even if the librettist’s characterisation is ambiguous to some degree. In the earlier scenes we are not always sure if she is more Nurse Ratched-like or more genuinely empathetic to Janet Frame’s predicament. As real-life New Zealand writer Janet Frame, Jayne Tankersley is given fewer opportunities to develop a compelling character, particularly for anyone unfamiliar with Frame’s reputation and personal story. But she provides a convincing focus for the plot’s exploration of the social attitudes and medical approaches to mental illness in New Zealand in the early 1950s. Tankersley’s focused vocal quality is rather penetrating at times without the vibrato needed to vary her timbre, but perhaps this is the vocal colour that the composer and writer intended for this role. Tone quality from both orchestra and singers is not helped by the acoustic. Christchurch’s performance venue, The Piano, is known for its opulent and helpful acoustics, but the set for The Strangest of Angels is a (deliberately?) claustrophobic front-stage box that somewhat cancels the spacious aural effect of the open wood-panelled stage. Although this relatively intimate venue was designed primarily for concert-style performances, I have seen several effective theatrical productions here. But with such an enclosed set, and with the fifteen-piece orchestra fitted into the floor space between the front row of seating, the overall acoustic effect emerges as rather dry. Even so, from a visual point-of-view, the set, with its implied electrotherapy lighting effects and its clever use of a revolving panel for scene changes, along with Eleanor Bishop’s supportive and unobtrusive direction, is very effective indeed. The Christchurch Symphony Orchestra players respond to Kenneth Young’s kaleidoscopic instrumental music with flair and commitment. Young’s ear for sonority and texture is realised with playing of often virtuosic and dramatic impact, fearlessly attacked with impressive ensemble. I just wished for some moments of respite from the harrowing pain of the opera’s dramatic framework; something musically uplifting that gives us a sense of hope. At the end, when the hospital equipment is transformed into a typewriter, dramatically we see the light of the successful literary career that Frame pursued after this episode. Should this have also been an opportunity for the music to once again sing with more optimism? Even so, as I leave the theatre I feel privileged to have witnessed the birth of this newest New Zealand opera, which features many moments to savour and even more for us to think about.  The Siege of Leningrad inspired Shostakovich's mighty Seventh Symphony The Siege of Leningrad inspired Shostakovich's mighty Seventh Symphony The mix of music and politics in the twentieth century got off to a blistering start with the première of Puccini’s Tosca in January 1900. Its turbulent background of politics and violence in 1800 Rome is a constant presence. The opera itself was the victim of political disturbances when a bomb threat delayed its première in Rome by a day. However, unlike the works and composers discussed in Part 1: 1700 – 1900 (see 16/3/2022 below), Puccini was far less interested in the politics than in the potential of his ‘shabby little shocker’ (as one reviewer called it) for theatrical melodrama. Even so, the issue of ‘Politics in Music’ is directly addressed in the opera’s Act II aria Vissi d’Arte (“I’ve Lived for Art”) in which Tosca, an opera singer, argues that she’s given her life to Art and to God, so why is He punishing her with all this blackmail, lechery and politics. Nor are Richard Strauss’s two one-act operas Salome (1905) and Elektra (1909) without political implications, although Strauss, like Puccini, was far more interested in their theatrical potential than their politics. Ironically, Strauss’s lack of direct interest in politics was the very cause of his political predicament during the Third Reich and after WWII. Strauss used his influence, as Germany’s most prominent composer, wherever possible to improve copyright law and the financial position of German musicians and composers; something that initially led him to support the Third Reich because of its support for cultural institutions. Despite remaining on generally good terms with the Nazi Party, Strauss resisted moves to blacklist Jewish musicians and was exonerated of any ties to the Nazi State during his denazification trial. The need to remedy what the Nazis believed to be the degeneration of German music resulted in a ‘cleansing’ – partly racial, partly stylistic – which affected numerous living German composers as well as attitudes to several who were long dead, particularly Mendelssohn and Mahler. Of the living, several left the country in the turbulent anti-Jewish 1930s – including Berthold Goldschmidt, Kurt Weill and Arnold Schoenberg, but many other Jewish composers such as Erwin Schulhoff and Pavel Haas, didn’t manage to escape the Holocaust and their surviving music became increasingly familiar as the century progressed. Paul Hindemith, was initially very much in political favour during the Third Reich, but by 1935 his music was suppressed. The anti-fascist political message of his opera Mathis der Maler was all too clear to the Nazis, with a plot that describes the painter Matthias Grünewald’s struggle for artistic freedom of expression during the repressive climate of the German Peasants’ War in the early sixteenth century. But the Nazis chose and promoted their own musical heroes and Hitler’s fixation with Richard Wagner’s music, ideology and personal characteristics is well-known. By association, Wagner came to represent the ideals of Naziism, a stigma that still remains to a degree, especially in the widespread public opposition to performances of his music in Israel, although the composer died almost half a century before the rise of the National Socialists. But Hitler distorted Wagner’s ideology to suit his own, just as hundreds of opera directors have done since the composer’s death. Hitler did the same with Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice which, unlike anything in Wagner’s musical works, is quite specific in its characterisation of the Jew, Shylock, as a villain. On his website, Israeli pianist and leading Wagner conductor Daniel Barenboim gives a very well-considered and penetrating summary of the anti-Wagner issue in Israel – but more on that in Part 3. If there is a single composer who can be identified as the leading exponent of the connection between music and politics, it’s surely Dmitri Shostakovich. Unlike almost every other Soviet Russian composer of real note among his contemporaries, Shostakovich remained a Russian resident throughout his life, while Stravinsky (before) and Rachmaninov (after) the 1917 Revolution, moved to Europe and then the USA. Although Prokofiev also left, returning in 1935, Shostakovich never considered leaving his homeland. The youthful exuberance of Shostakovich’s First Symphony gave way to the state-commissioned Soviet propaganda of the Second and Third. The primal suffocating scream that opens the Fourth leads to an explosive, almost traumatic outpouring in an epic symphony which was withheld by the composer for twenty-five years for fear of retribution, followed by the ironic triumph of the Fifth. In the 1940s, Shostakovich’s experience of oppression from all sides was openly expressed in his chilling and turbulent ‘war’ symphonies – The Leningrad (Seventh) written in that city during its siege by the Nazis, followed by the grief-stricken despair of the Eighth with its jack-booted third movement, and the crushing (both physically and mentally) totalitarian Adagio section of its Finale. In England, Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral Symphony, unlike its Beethoven namesake, takes no delight in the beauty of the countryside, but, rather, laments the fallen WWI soldiers who now lie beneath the battlefields of Europe. And his Sixth Symphony’s violent and disturbing character is widely thought to express the composer’s reaction to the deployment of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even Vaughan Williams’ popular The Lark Ascending, begun before the war as an English county idyll, ended, in its 1920 orchestral form, as an elegy for a lost world and lost lives. In 1943 Michael Tippet was imprisoned for his refusal to undertake even non-combatant war-related duties during WWII. However, his Oratorio A Child of Our Time expresses his reaction to the Nazi’s violent pogrom against Jews, although its inclusion of African-American spirituals protests against all forms of oppression, including his own imprisonment, and also underlines the subversive political motivation of the spirituals themselves. Benjamin Britten’s political beliefs are well-known, particularly his total commitment to pacifism and the futility of War. His War Requiem, juxtaposing the text of the Latin mass with poems by Wilfred Owen, is among his finest works. And Britten’s 1970 opera Owen Wingrave further debates the morality of war; its subject was deliberately chosen as a protest against the Vietnam war. The musical protests of that time in popular music should also not be forgotten. Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Pete Seeger and Joan Baez were among many singers and songwriters whose music had a profound effect on changing attitudes to war. Others, including John Lennon (Give Peace a Chance; Imagine) continued the anti-violence message which was taken up by many others in the last decades of the twentieth century. Sadly, their legacy seems to have wilted in the twenty-first century as, once again, aggression is seen as a valid means of repressing opposing ideologies. Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki’s 1961 string orchestra piece, originally titled 8’37”, was intended as an exploration of new sonorities as the composer developed his very personal musical language. After hearing the work performed, Penderecki became aware of its intense emotional charge and renamed it Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. Then, in 1992, another Polish composer, Henryk Górecki, shot to fame when a new recording of his fifteen-year-old Symphony No. 3 – Symphony of Sorrowful Songs beat all sales records for a recording of symphonic music. The symphony comprises three ‘laments’ which reflect on the Holocaust, and particularly on the lives that were lost in the camps that were established by the Gestapo in the composer’s homeland. Finally, the contemporary American minimalist John Adams’ music is full of political content. Among his many politically motivated works, three of his operas stand out for their radical reactions to relatively recent major historical events. Nixon in China (1987) analyses how mythology can be created through propaganda and accepted as truth; The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) remains Adams’ most controversial work and still draws misguided accusations of “catering to anti-American, anti-Semitic and anti-bourgeois prejudices”, as well as being subjected to public protests every time it’s revived; and Doctor Atomic (2005) focuses on the extreme anxiety and stress of those involved in the lead-up to the testing of the first atomic bomb in 1945. These examples of politics in music are by no means exhaustive, but they are proof enough against those who might suggest that politics has no place in music. Any such glib claim runs counter to the inherent artistic expression in music and other artforms.  “Viva Verdi” – “Vittorio Emmanuelle Re D’Italia” “Viva Verdi” – “Vittorio Emmanuelle Re D’Italia” For the last few weeks the music world has been quite a chaotic game of musical chairs since Russia started to invade Ukraine. Prominent Russian musicians have had their concerts and contracts cancelled in the west; the Ukrainian National Anthem has been performed before performances of Verdi’s Don Carlos at New York’s Metropolitan Opera; the Berlin Philharmonic dedicated their Mahler Resurrection Symphony performances to the people of Ukraine and projected the Ukrainian flag onto the wall of their concert hall; the body of the assassinated Siegfried in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung was enshrouded in the Ukraine flag during performances at Madrid’s Teatro Real; and Russian musical works have been replaced by other music in concerts and broadcasts in many places, including here in New Zealand. Some say that “politics has no place in music”, but let’s think this through! Political intervention from both church and state were certainly factors in every aspect of music before the eighteenth century, but let’s consider just a few of the many examples from the Baroque period onwards . . . George Frideric Handel chose many of his opera subjects for their potential to exalt historical or legendary kings in support for England’s sometimes unpopular German-speaking monarchy; and that’s not to mention Handel’s many Coronation Anthems and other works designed to celebrate royal occasions and which also have political associations. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s choice of Beaumarchais’ play Le Mariage de Figaro as the subject for an opera represented the growing disillusionment with the ruling classes throughout Europe. In Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus, Mozart convinces the censors that he has removed everything contentious from the plot and says that he hates politics. But Beaumarchais’ condemnation of aristocratic privilege has always been characterised as foreshadowing the French Revolution. Georges Danton, one of the Revolution’s leading figures, said that Beaumarchais’ play “killed off the nobility”, and Napoleon later referred to Le Mariage de Figaro as “The Revolution already in action”. Other operas by Mozart explore similarly political ideas – think about the concept of ‘Droit du Seigneur’ in Don Giovanni. Rossini used another Beaumarchais play, Le Barbier de Séville (to which Le Mariage de Figaro is the sequel), while Donizetti used similarly revolutionary and other political subjects by Walter Scott and Friedrich Schiller. And surely the obvious parallels with the situation in Italy, to the Swiss hero William Tell’s resistance to Austrian rule, are no coincidence in Rossini’s great final opera (1829). Beethoven originally dedicated his Eroica Symphony to Napoleon, seeing him as the people’s liberator from the yoke of the old feudal world of aristocratic subjugation and, in Beethoven’s own case, from the servitude of court musicians. But the Eroica dedication on the symphony’s title page was unceremoniously scoured out by the composer when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor. Many of Beethoven’s greatest works maintain a strong thematic trend expressing struggle against various forms of oppression and subjugation, leading to triumph at the end. The Eroica is a prime example of that, as are also the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies, the opera Fidelio, the incidental music to Goethe’s play Egmont and much else. Mention of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony reminds us that, despite it being a work by a German composer, its opening motif was used by Winston Churchill to introduce his WWII radio broadcasts. With the motif’s dit-dit-dit-dah being Morse code for ‘V’ (for Victory), Churchill replicated it visually in his famous ‘V’-shaped finger gesture at the time. At the end of 1944 that same Winston Churchill turned his focus of attack to the Greek partisans who had fought on Britain’s side in the war and who had succeeded in pushing the Nazis out of Greece. Apart from those killed at Britain’s hand in this campaign, a young composer and member of the Greek People’s Liberation Army, Iannis Xenakis, lost half his face in Churchill’s offensive. Some years later, musicologist Harry Halbreich, in reference to Xenakis’ now well-established reputation as a leading musical revolutionary, compared his music to Beethoven’s as being “austere, uncomfortable, and never sentimental” as well as being “highly expressive, courageous and energetic”. Further political content can be attributed to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony when we consider that the composer once commented that it expresses words written about murdered French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat “We swear, sword in hand, to die for the republic and for human rights”. Conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt says about the Fifth: "This is not music; it is political agitation. It is saying to us: the world we have is no good. Let us change it! Let's go!" And conductor and musicologist John Eliot Gardiner’s research has found that many of the themes in Beethoven’s symphonies are based on French revolutionary songs. Giuseppe Verdi, even more so than Mozart, Rossini and Donizetti in the world of Italian opera, was an actively political animal. There can be little doubt that the famous prayer for freedom, the Chorus of Hebrew Slaves, in his third opera Nabucco (1842), expressed his own deep desire to see the unification of Italy and the end of Austrian rule – “O mia patria, si bella e perduta” / "O my country, so beautiful, and lost”. The sentiments expressed in several of Verdi’s other operas – e.g. Attila, I Lombardi and Giovanna d’Arco – are even more obviously politically motivated. Chants of “Viva Verdi” both inside and outside Italian opera houses were hardly subtle in their true motive – the letters of Verdi’s name standing for “Vittorio Emmanuelle Re D’Italia”; and the Sardinian ruler, Victor Emmanuelle, did indeed become the first king of an independent and unified Italy in 1861, the same year that Verdi himself was elected to the first Italian parliament. On the opposite side of the Austrian-Italian conflict, even Johann Strauss I needs mention for his most famous composition as his Radetzky March of 1848 was written to celebrate Austrian Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky’s victory in quashing an Italian uprising at the battle of Custoza. Victor Hugo’s 1832 play Le Roi s’Amuse was banned for fifty years after its one and only performance because it was seen as a deliberate insult to Louis-Philippe, the French king of the time. When Verdi used Hugo’s play for his opera Rigoletto in 1851, he was forced by the censors to change the character of the French king into an Italian duke. Then, in 1859, further political censorship resulted in Verdi altering his opera Gustavo III about the real-life assassination in 1792 of the Swedish king, to become Un Ballo in Maschera about the assassination of a fictional governor in colonial Boston! And one of Verdi’s greatest operas, Aida, with its conflicts of personal vs. political loyalties and betrayals, has thought-provoking parallels with the dilemmas that Russian musicians must surely be facing this month. Before we leave the nineteenth century, passing over numerous other politically motivated, or at least politically expressive musical works (let’s keep Richard Wagner for consideration in the twentieth century), there are two other obvious examples by great and well-known composers. Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 are both unashamed and partisan celebrations of significant battle victories that played a part in the political shaping of Europe. Then, as the nineteenth century progressed, the Nationalist Movement comprising non-Austro-Germanic composers (Chopin, Smetana, Dvořák, Grieg and others) stated their claims to cultural independence, and culminated in the 1890s with Sibelius’s political protests, in works such as Finlandia and Karelia, against Russian autocracy.  The announcement last year of the impending release of Steven Spielberg’s new movie version of West Side Story was an exceptionally exciting prospect which I keenly anticipated for several months. But, exciting as that prospect has been for me, this brilliantly reimagined movie has not yet realised a break-even financial return at the box-office. As I write this, we don’t yet know if it will make the Oscar nominations, but maybe if it gets an award or two it will surely repeat the success of Cabaret in 1972 when, in New Zealand at least, the original release passed by almost unnoticed until its haul of eight Oscars brought its immediate and hugely successful return to our screens. I saw the new West Side Story at the start of January at Christchurch’s Academy Gold Cinema, one of the very few daytime showings in recent years when I’ve been in a movie theatre that was completely sold out. And, while I loved the movie as a whole, I was initially rather disappointed by the musical impact – or lack of it. The emotional clout of this great score just wasn’t there! A few days later I listened to the music soundtrack at home on my own sound system and the experience was totally different. Everything, as my wife and I both agreed, was so much better. The singing was heartfelt, and the orchestral balance was much more immediate and powerful. What had seemed rather lame in the cinema, came fully to life in my living room. I can only presume that the Academy Gold didn’t have the volume level turned up high enough. A few days later, Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth at the Lumière cinema in the Christchurch Arts Centre had all the audio impact one could wish for, which added so much power and atmosphere to that movie. Although the 1961 West Side Story (Best Picture plus 9 other Academy Awards that year) remains a classic, nothing about this new 2021 version is inferior – and much is superior, further demonstrating that Shakespeare’s timeless masterpiece Romeo and Juliet (1595) via West Side Story (1957→1961→2021) remains as topical and relevant as ever. Spielberg’s movie fully communicates the profound humanity of the story – it has the rare quality of compelling our sympathy for every character and enabling us to understand the motivations of every side of the conflict. This is partly the result of setting the production in the reality of Manhattan’s Upper West Side slum clearances on San Juan Hill in the late 1950s, exactly at the time when West Side Story was first staged, and which displaced over 7000 families. Ironically (deliberately?), the world premiere of this new movie screened at Lincoln Centre’s Rose Theatre on the very site of the slum clearances where the movie is set. As I listen again to that stunning new soundtrack, I hear so much more characterisation in every part than ever before; even single lines and phrases from individual ensemble characters are teeming with personality, expression and heart. Officer Krupke is the most obvious example with its wonderfully-conceived improvisatory beginning, but characterisation and individuality are equally to the fore in every ensemble piece from The Jet Song, to America, and from Cool to the ensemble sections of I Feel Pretty. If some of the orchestrations sound a bit homogenous as recorded (where are the all-important guitars in America that Bernstein was so insistent on hearing clearly in his own 1984 recording?), all the instrumental colours and originality of the composer’s and his assistants’ imaginations astonish anew; and the vocal rhythms and textural clarity of the five individual lines in the quintet version of Tonight are simply stunning. As usual with movie musicals (although West Side Story is more than just a musical), much of the musical soundtrack was pre-recorded and used as playback during filming, but I found Ansel Elgort and Rachel Zegler (Tony and Maria) so convincing in their singing of One Hand, One Heart that a bit of research revealed that several songs (One Hand, One Heart; Somewhere; A Boy Like That/I Have a Love; parts of Maria) were indeed sung and recorded live on set during filming. And what a stroke of genius to make the store owner Doc into the Puerto Rican Valentina (played, incidentally, by Rita Moreno, the 1961 film’s Anita) – her performance of Somewhere brought a tear or two, even if, in 1961, she had a ghost voice for A Boy Like That. For this new version, arranger David Newman has retained and respected the 1961 film’s superb original orchestration with a few adaptions and enhancements, all to positive effect. The order of the songs is slightly different from both the original stage score and the 1961 movie – the placements of Cool (here with its chilling undercurrent of commentary on America’s gun culture) and Officer Krupke both make convincing sense in 2021. America retains the Puerto Rican boy vs. girl of the 1961 movie as opposed to the less potent girls-only of the stage musical. And the addition of the Puerto Rican anthem La Borinqueña, sung by the Sharks in the opening sequence, gives them a sense of purpose, personality and validity that balances their status with the Jets in the following Jet Song. The amount of untranslated Spanish in the movie gives the Puerto Rican characters new authenticity, and Tony Kushner’s screenplay brings the original rather stagey dialogue into the twenty-first century. Some of that dialogue restores one or two of the grittier elements of the stage script (“sperm to worm”) that were softened in the 1961 movie. Justin Peck’s choreography is also less stagey than in 1961 – the sizzling spectacles he provides with the help of equally spectacular cinematography in the Jet Song and the Dance at the Gym are exhilarating, and the way America races through the streets instead of being confined to a rooftop (1961) is electrifying! I really need to see this movie again, but I also need to know that the cinema will give it the audio presentation that it deserves. |

AuthorTony Ryan has reviewed Christchurch concerts, opera and music theatre productions and many other theatre performances since the mid 1990s. ReviewsTony has presented live and written radio reviews of numerous concerts, opera and other musical events for RNZ Concert for many years. An archive of these reviews can be found at Radio New Zealand - Upbeat

His reviews of opera, music & straight theatre and numerous reviews of buskers and comedy festival performances are available at Theatreview. An archive of Tony’s chamber music reviews is held at Christopher’s Classics He has also reviewed for The Press (Christchurch). Links to Tony's Press reviews are listed below: 2024 Songs for Helen – Music by Chris Adams 2022 A Barber and Bernstein Double Bill – Toi Toi Opera The Strangest of Angels – NZOpera Will King (Baritone) and David Codd (Piano) – Christopher's Classics 2019 Ars Acustica – Free Theatre Truly Madly Baroque – Red Priest The Mousetrap – Lunchbox Theatre Iconoclasts – cLoud Last Night of the Proms – CSO 2018 An Evening with Simon O’Neill NZSO Catch Me If You Can – Blackboard Theatre Brothers in Arms – CSO Fear and Courage – CSO Sin City – CSO Don Giovanni – Narropera at Lansdowne Mad Hatter’s Tea Party – Funatorium Weave – NZTrio Tosca – NZ Opera 2017 Sister Act – Showbiz Broadway to West End – Theatre Royal Chicago – Court Theatre Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 5 – CSO Homage – CSO Last Night of the Proms – CSO SOAR – NZTrio Pianomania – NZSO Rogers & Hammerstein – Showbiz Songs for Nobodies – Ali Harper The Beauty of Baroque – CSO Travels in Italy – NZSO Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed